Yes, yes, it is Wednesday but my colleagues in the group are a remarkably tolerant lot. At least, I hope so.

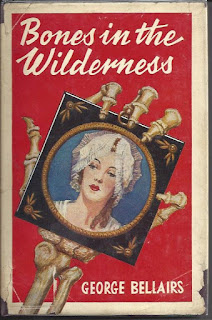

The two novels I want to look at came out after the war, in 1952 (John Bude's Death on the Riviera) and 1959 (George Bellairs's Bones in the Wilderness). The first was written at about the grimmest time of Britain's post war history - the rationing was worse than it had been during the war, the Labour government had raised taxes to a phenomenal level, rebuilding was not going on fast enough and the unions were flexing their muscles. By the time of the second one, life had improved considerably. Rebuilding had proceeded apace, rationing had gone but the food remained as limited as before and various price controls prevented growth and development in retail. People had begun to travel (almost exclusively to European countries unless you were in the military or the diplomatic) and noted that the countries that had been occupied or defeated in the forties were faring much better than Britain, unoccupied and victorious.

These were also the years when Elizabeth David published her first few highly successful books: A Book of Mediterranean Food (1950), French Country Cooking (1951), Italian Cooking (1954) and Summer Cooking (1955). Slightly less well known but equally important was Plats du Jour by Patience Gray and Primrose Boyd.They all brought the joys and pleasures of exciting and colourful food to the British feeling, many of whom were somewhat oppressed by the reality of eating in this country. Two other books need to be mentioned in this connection: Nancy Mitford's completion of her saga of English aristocrats before and after the war: The Blessing (1951) and Don't Tell Alfred (1960).

What these books had in common was the glowing depiction of France, particularly its southern parts, though Paris as well in Nancy Mitford's novels, the colours, the scenery, the food and, not least, the drink - wines, brandies, liqueurs, aromatic coffee - so different from the watery beer and undrinkable muddy slush that passed for coffee in English inns and restaurants.

The two detective stories I have just read and referred to above fit into this category very neatly. They are tales of murder and detection but they are also travelogues of the Riviera, other parts of France and glorious accounts (especially Bones in the Wilderness) of the most wonderful meals and wines. Death on the Riviera has less of that but there are references of breakfasts on the terrace with coffee and rolls, the odd lunch of a fluffy omelette aux fines herbes and glorious wines. Indeed Bellairs's Superintendent Littlejohn and Sergeant Cromwell (who is interested enough in everything he sees and tastes to make copious notes) find themselves several times somewhat the worse for wear.

Interestingly, both these books talk about people being allowed to take £100 abroad in cheques or cash and this is not seen as being very much despite the overvalued pound sterling. After the Labour victory in the mid-sixties, this amount was reduced to £50 which was worth even less after the devaluation of 1967. (Though the French devalued in 1969 so what went around came around.)

It's hard to find out anything about George Bellairs except that his real name was Harold Blundell, that he lived from 1902 to 1985, was a bank manager from Rochdale until he gave that up to write detective stories when he also moved to the Isle of Man. The English Wikpedia does not mention his travels in France, which judging by this and at least one other book that is referred to, must have happened several times. For that one must turn to the French entry, which tells us of his degree from the London School of Economics, his success in the banking business, his move to the Isle of Man and his travels in Europe. Inspector, later Superintendent Littlejohn, we are told is sometimes assisted by his wife Letty as crime happens when they travel to France or the Isle of Man. Not in Bones in the Wilderness, where he is assisted by Sergeant Cromwell but the descriptions of travel, of scenery and of food remain as luscious as ever.

Here is just an ordinary luncheon:

"Excellent eel soup, Barbecue steaks and rice, after an hors d'oeuvres of tomatoes, peppers, green olives, sausage and fish. Then, fruit and goat's cheese. All washed down with the fulsome red and white Mâcon from the vineyards of Pont de Veyle." Even in 1959 most readers would have found this overwhelming and unreachable.

The plot, which is secondary to the travelogue and gastronomic description is quite good and tightly put together, despite the endless dashing across France and back again. Curiously, the characters are either extraordinarily good looking or quite appallingly repulsive.

John Bude (1901 - 1957) is also a pseudonym, in this case of Ernest Elmore, a theatre producer and director who did go to southern France quite a few times, as Martin Edwards explains in his excellent and highly informative introduction.

A number of his detective stories have been reprinted by the British Library and, speaking quite honestly, I am not sure he deserves such accolade. They are good enough but the plots tend to be convoluted with loose ends while the character of Inspector, later Chief Inspector, then again Inspector but of Scotland Yard Meredith is one of the most humdrum of the humdrums. In one of the earlier novels he has a wife and a son who add a bit of colour to his personality but these disappear not even to be mentioned in the later ones.

Death on the Riviera, which does give a glorious picture of Menton and its environs consists of two plots really, one to do with a gang of money forgers, the other with a more domestic murder, and somehow never quite unites them. The same people are involved but at least one of the gang is forgotten in the general round-up and the highly complicated murder and alibi creation appears to have a very weak reason for it. Still, there are splendidly amusing French police officers and Acting Sergeant Freddy Strang, who is allowed to be quite bright, finds true love. And there is that fluffy omelette.

Wonderful to read another Bellairs fan . My late father worked with him in Martin's Bank and found him a delightful colleague . Blundell told dad that he made only enough money from the books to pay for these holidays . He was an expert on currency regulations whis=ch were very irksome. Great news that both British Library and Ipso books are reissuing so many titles this year .

ReplyDelete